Please note: This blog post is under construction

When adoption comes to mind, it is often associated with positive images of family and love. For many adoption triad members (birth parent, adoptee, adoptive parent), adoption is associated with painful feelings, and for some, traumatic experiences. Debilitating trauma symptoms occur because adoption triad members’ brains and bodies act as if the traumas are happening in the present. Unfortunately, the very narrow definition of what society and the mental health community constitute as a traumatic experience for a person to be diagnosed with a trauma disorder does not include adoption trauma experiences. To fully support adoption triad members, the reality of their feelings and adoption trauma symptoms needs to be validated. This includes acknowledging that many adoption triad members have complex post-traumatic stress disorder from their relinquishment and adoption experiences. Due to this blog post discussing a wide range of adoption traumas, relinquishment trauma will be the term used for the adoptee trauma resulting from separation from their birth mother. This blog post explores adoption triad members’ relinquishment and adoption traumas, adoption trauma symptoms, complex post-traumatic stress disorder as a mental health diagnosis, and complex post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms experienced by adoption triad members.

This blog post on adoption traumas and complex PTSD is for educational purposes only. Individuals who believe they have complex PTSD should seek help from a trained trauma therapist for a diagnosis, treatment plan, and trauma therapy. Individuals should not self-diagnose due to a lack of knowledge on clinical terms for symptoms, and many mental health conditions have overlapping symptoms.

This blog post should not be generalized for all adoption triad members.

Society’s Fictitious Beliefs Traumatizing Adoption Triad Members

Society’s view of adoption as a purely positive win-win experience interferes with acknowledging that there are traumatic experiences that are relinquishment and adoption-related. Traumatic beliefs include beliefs that birth parents should not look back because they did a “good thing”, adoptees are “disloyal” for wanting to talk about their adoption experiences, and adoptive parents should raise their adopted child “as if” they were born to their family. Adopted children of color have been placed with white adoptive parents who “do not see color” because having loving parents is all the child needs.

This lack of acknowledgment of adoption triad members’ real-life experiences results in a lack of supportive and therapeutic services during crisis pregnancies and post-adoption. Clinicians without adoption issues training can easily believe the misconceptions and stereotypes of adoption. This can result in the clinician downplaying the impact of relinquishment and adoption, resulting in a non-trauma approach to psychotherapy. When clinicians are not adoption-informed, they are not asking questions related to adoption during their history taking. Thus, adoption trauma symptoms are overlooked because there is no awareness of birth parent trauma, adoptee trauma, or adoptive parent trauma. Without an accurate diagnosis, traumatized adoption triad members are isolated with their mental health struggles without a clear path for healing. Many adopted youth are diagnosed with behavioral disorders (oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder) when a diagnosis of developmental trauma disorder would be more appropriate. Without realizing it, mental health and adoption professionals have been the perpetrators of adoption-related traumas. To learn more about adoption-competent therapy, visit the adoption-competent blog post.

With so many people and society not acknowledging adoption traumas, it leads adoption triad members to be in chronic misattunement with others and society. This misattunement causes adoptees, birth parents, and adoptive parents to become disconnected from their feelings and identity because their reality is not acknowledged.

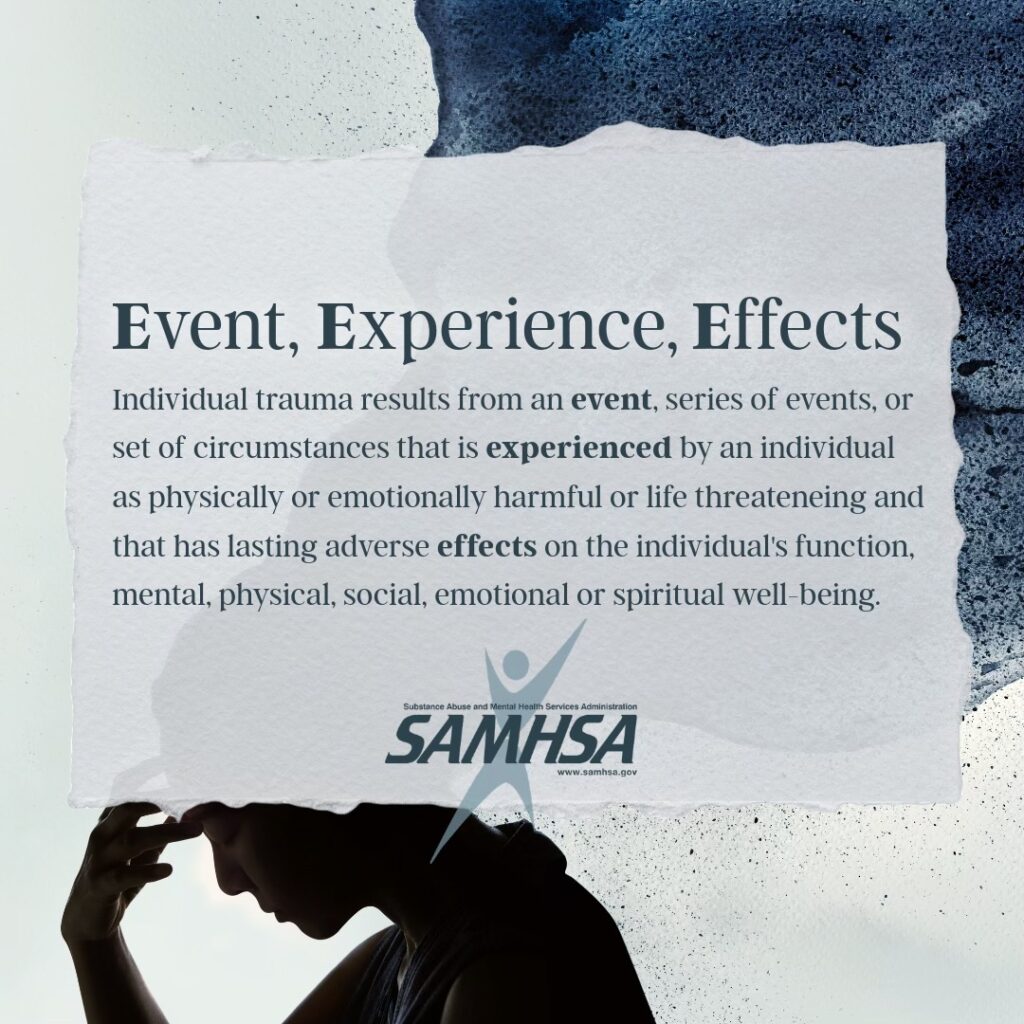

Broadening the definition of trauma to include horrific relinquishment and adoption experiences is the first step to acknowledging what adoptees, birth parents, and adoptive parents have experienced. When the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s 3 Es of Trauma -Event, Experience, Effect paradigm [FN 1] is applied to relinquishment and adoption traumas, it validates adoption experiences as traumatic events. The 3E’s paradigm premise is that if an individual has lasting trauma symptoms (EFFECT) from the event, it was subsequently a traumatic experience. The 3 E’s trauma paradigm recognizes that the same event may result in one individual developing trauma symptoms while another individual could have been impacted but not develop trauma symptoms. The 3 E’s of trauma paradigm explains why some adoption triad members are less traumatized by relinquishment and adoption experiences and why other adoption triad members have significant trauma symptoms.

The 3Es of trauma paradigm uses a broad definition of traumatic events. Examples of traumatic events include living parents with mental health struggles, psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, racial traumas, daily living traumas (homelessness, unsafe neighborhood, poverty), emotional neglect, estrangements, and traumatic in-utero experiences. EXPERIENCE in the 3 E’s trauma paradigm includes the severity of the trauma event and the availability of support when the trauma occurred. An example is an adoptee who is a person of color raised by white parents, would have a different racial experience than if the adoptee had been raised with adoptive parents who were of the same race/ethnicity. Another example is a birth mother could have profound trauma symptoms from the crisis pregnancy, and losing her child to adoption, but a birth father who did not psychologically think of himself as a father at the time of his child’s birth would have been impacted, but may not have trauma symptoms. Having supportive people who acknowledge an individual’s narrative and support their pain without judgment can help lessen the intensity of trauma symptoms. Experience includes how a person labels and assigns meaning to their experiences. If an individual feels shame, it can intensify trauma symptoms. Conversely, self-compassion can lessen trauma symptoms. The EFFECT in the 3 E’s trauma paradigm is the resulting trauma symptoms. The greater the number of trauma experiences, the severity of the events, and the lack of support during traumatic events creates a compounding effect on the brain and body of the trauma survivor.

Abbreviated List of Adoption Trauma Experiences

Birthparent Trauma Experiences

Loss of their child to adoption (voluntary and involuntary surrender)

No information on how their child is doing

Not being involved in their child’s life as they grow up

Kicked out of family home, school, or employment due to a crisis pregnancy

Sent away to a maternity home or other living arrangement due to a crisis pregnancy

Psychological abuse from family members and professionals (adoption and medical)

Contact with their child and adoptive parents is ended by the adoptive parent in an open adoption relationship

Reunion experience ends with their child not wanting a relationship with them

Family acts “as if” their child lost to adoption does not exist

Birth father learning about his child who was adopted after the adoption finalization

Adoptee Trauma Experiences

Abandoned as an infant or child

Living in foster care or an orphanage

Relinquishment and separation from their birth family

Limited or no information on birth family and reasons for adoption

Loss of genetic mirroring and relationships with their birth family

Learning adopted as a teen or an adult (late discovery adoptee)

Adoptive parents raise their child “as if” the birth family does not exist, and adoption has no impact on them

Being a person of color raised in a white family and having the racial/ethnic identity of the adoptive parents and not their race/ethnicity

An open adoption relationship ends with the birth family stopping all contact

Reunion ends with their birth family not wanting a relationship with them

Adoptive Parent Trauma Experiences

Unresolved infertility, miscarriage, or stillbirth that negatively impacts their relationship with their adopted child

Parenting a child with developmental trauma who rejects their care and love

Their child’s birth parent does not acknowledge the adoptive parent as the primary parent in an open adoption relationship

Rejection from extended family for adopting a child with mental health struggles which is disruptive to extended family gatherings

Secondary trauma from hearing their child’s trauma experiences

Trauma from interacting with their child during extreme emotional deregulation, psychological abuse, or physical abuse from their child

Adopted child rejects adoptive parents and wants to return to their birth family

Both complex PTSD and adoption traumas have similar origins, with both stemming from interpersonal traumas. While there is insufficient research on evidence-based clinical practices for healing from adoption traumas [FN2], there is extensive research on psychotherapy treatment for complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) [FN3]. Thus, complex post-traumatic stress disorder psychotherapy treatment models should be considered for the treatment of adoption traumas. Since healing adoption trauma symptoms using a complex post-traumatic treatment approach is a topic worthy of a book, this blog post is just an overview of the topic. To give this topic justice, it will be presented in two blog posts. This first blog post will discuss adoption traumas, an introduction to complex PTSD, and trauma symptoms common to adoption triad members. A subsequent blog post will explore treatment approaches for adoption trauma using the 3-stage treatment approach to healing C-PTSD.

Adoption Traumas Resulting in Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms

Traumatic experiences fall into two categories -commission: things that happened to a person, and the traumas of omission-things that did not happen. Traumatic commissions include physical abuse, sexual assault, psychological abuse, racial oppression, estrangement from family, refugee experiences, losing a child to adoption, safe haven abandonment, relinquishment trauma, and living in an unstable environment (foster care, orphanage, maternity home).

A very common traumatic commission is adoption microaggressions [4 FN]. Microaggressions include cruel things that are said or done to adoption triad members. This includes: statement to adoptive parent, “Do you have any real children?, statement to adoptee, “What do you know, you’re a messed up adoptee.”, statement to birth mother, “You shouldn’t have any bad feelings about the adoption, you know you did the right thing”. Transracial adoptees have been called Oreo, banana, Twinkie, and apple because they don’t act like the stereotypical person of their race/ethnicity. Another example of an adoption trauma microaggression is when adoptee’s extended family shows favoritism to biological relatives.

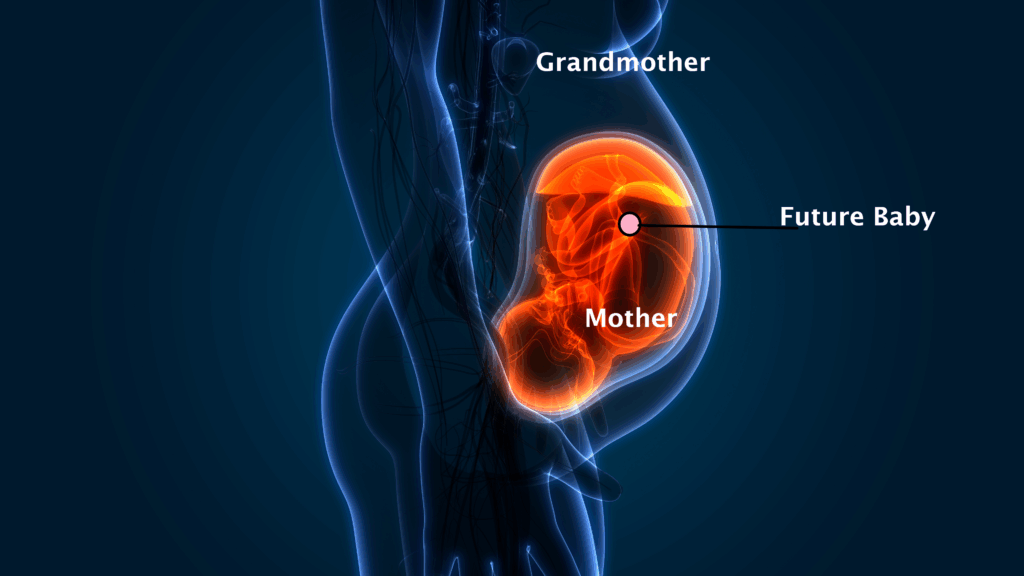

A wide definition of traumatic experience of commission includes toxic stress of the in-utero environment. Infants are born with the same neurochemistry as their mothers. If an expecting mother experiences trauma during her pregnancy, it can result in the infant being born with the same trauma neurotransmitters, resulting in a child growing up with a predisposition for depression, anxiety, or PTSD. This helps to explain why so many adopted persons suffer from anxiety, depression, and trauma disorders. High levels of maternal stress during pregnancy is associated with children having delayed development in cognitive and motor functioning [FN 5]. Attachment issues can begin in utero when the pregnant mother does not attach to her baby. Additionally, research has shown that trauma on both the mother’s and the father’s side can cause a predisposition for a trauma mental health diagnoses for future multiple generations. [FN 6].

Traumatic Omission in Adoption

Traumatic omission includes neglect, and absent or emotionally unavailable caregivers. These conditions cause low self-worth and struggles with attachment. The adoption triad members who seem to struggle the most are the ones whose parents were absent or had mental health struggles. It is not unusual to hear stories from birth mothers that their mother was absent in their childhood, because of death, estrangement, or was emotionally absent due to mental health struggles, including addictions. Closed adoptions are omission traumas because of the estrangement, no information, or limited information. An adoptive parent may have trauma from not having a birth child.

Omission trauma for adoption triad members includes traumatic invalidation and betrayal trauma. Traumatic invalidation occurs when an individual’s environment repeatedly or intensely communicates that the individual’s experiences, characteristics, or emotional reactions are unreasonable and/or unacceptable. It is especially harmful when family, loved ones, and the community that the adoption triad members rely upon are the source of the trauma. It is cruel when people act as if relinquishment and adoption never happened. It is traumatic for birth parents to have a child whom their family does not acknowledge, and they are expected to get over their grief.

Adoptee trauma includes when adoptees are expected to act as if their life started when they joined their adoptive family. They are treated harshly if they discuss what it feels like to be adopted or wonder about their birth family. When adoptive parents do not give their adopted child all the information they have on the reasons for relinquishment and their birth parents, it is an omission trauma. Learning as a teenager or adult that you are adopted (late discovery adoptee) is a cruel traumatic invalidation. Lack of information given to adoptive parents by adoption professionals on the birth family is an omission trauma.

A horrific traumatic invalidation is when adoptive parents raise their child as if they were white when they are a person of color. When a child’s race and ethnicity are denied, it is about the adult’s need for denial and their willingness to sacrifice their child’s self-worth, identity, and mental health. This traumatic invalidation includes when adoptive parents do not respond to adoption and racial microaggressions towards their child.

Traumatic invalidation results in a denial of reality and feelings while interacting with the invalidators. Individuals become people pleasers and chameleons because their “support system” will not acknowledge their truth. It creates a persistent fear of not being accepted. With the lack of acknowledgment of the reality of their lived experience, individuals do not know how to interpret the messages from their environment or internal messages from themselves.

Betrayal Trauma in Adoption

Betrayal trauma [FN7] is a very common experience of adoption triad members. Family members who were needed for support during an adoption triad member’s most difficult life experiences were often the perpetrators of the traumatic experiences. Examples of betrayal trauma include a birth mother who was verbally abused or kicked out of her home due to a crisis pregnancy. Adoptive parents’ refusal to talk to their child about their birth family is a betrayal of the basic emotional needs of the adoptee. Adoptive parents who are told they are the cause of their child’s mental health struggles while minimizing the impact of the child’s early trauma experiences before their child’s placement into their family is traumatic.

Introduction to Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Judith Herman was the first to propose complex post-traumatic stress disorder in her book Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror (1992). [FN 8] Herman noticed that the trauma survivors she was working with who experienced prolonged trauma exposure had more trauma symptoms than individuals with single-incident traumas (e.g., violence from a stranger, natural disaster). Prolonged trauma experiences created additional symptoms because the source of the abuse was often an individual who should have been supportive, the victim was blamed, and the victim was unable to escape the abuse. Additional trauma symptoms Herman identified include relationship difficulties, affect dysregulation (difficulty or inability to regulate emotional responses, resulting in intense and/or prolonged emotional reactions), dissociation, amnesia, severe negative self-concept, and alteration in their perception of the perpetrator. Individuals with complex PTSD struggle in their lives in a more profound way than trauma survivors of single-incident trauma.

Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror also offered groundbreaking insights into trauma and trauma treatment. Long before the ACES research study [FN 9], Herman recognized the cumulative effect of traumatic events and traumatic environments (e.g. intergenerational traumas due to mental health struggles, racial traumas, sexual orientation traumas, genocide, systematic oppression, extreme poverty, homelessness, and severe bullying) which often result in more symptoms and symptom severity. Additionally, Herman saw trauma survivors often believed something was wrong with them and that they caused the abuse, since the source of the trauma was a loved one. She noted that living through traumatic experiences early in life created trauma symptoms (freeze, people pleasing) that interfere with self-protection, setting the stage for individuals to be revictimized late in life. Herman saw that trauma survivors’ trauma symptoms included inaccurate beliefs about the abuser, often including an over-identification with the abuser.

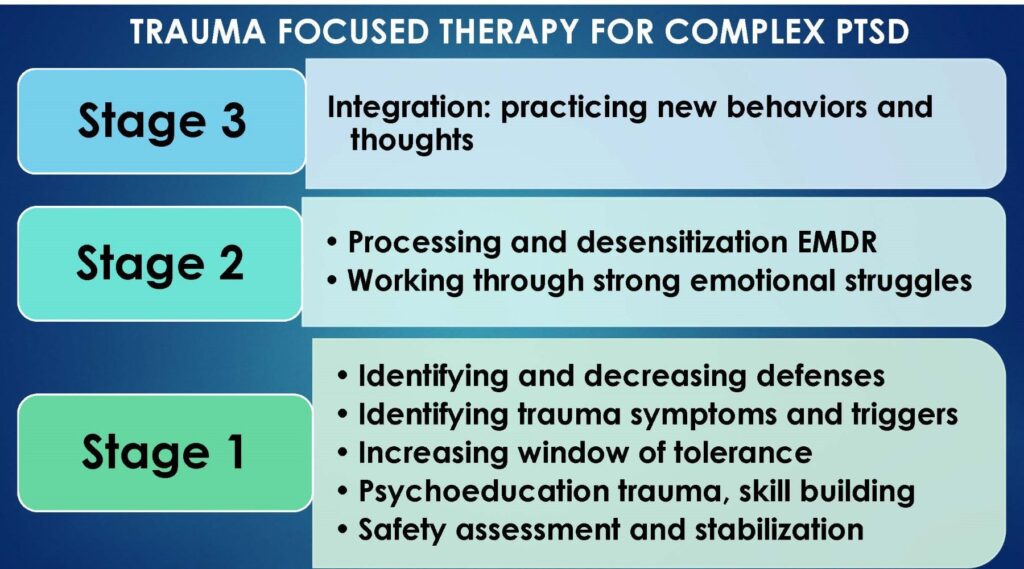

In addition to broadening the understanding of trauma symptoms and traumatic events, Herman was the first to delineate a three-stage approach to trauma treatment. She believed psychotherapy should focus on the relief of trauma symptoms. Treatment should not be about the telling the details of the traumatic experiences which is often retraumatizing.

Francine Shapiro, the originator of Eye Movement and Desensitization Reprocessing Therapy (EMDR), contributed further to the discussion by expanding the definition of traumatic experiences. She elaborated that there are two types of traumas – big T traumas and little t traumas [FN10]. Big T traumas include physical abuse, war, sexual assault, disasters, accidents, and watching someone die. Little t traumas include psychological abuse, bullying, shaming, and cruel invalidation. Shapiro’s work demonstrated that victims of little t traumas can exhibit trauma symptoms as severe as those experienced by victims of big T traumas.

Herman, Shapiro, van der Kolk, and other trauma researchers and therapists’ approach to healing from trauma does not require focusing on the details of traumatic events. Instead, trauma-informed therapy helps individuals decrease the impact of trauma symptoms on their mind and body. The goal is to prevent survivors from being hijacked by their emotions, sensations, and reactions. Healing is perceiving others and their environment accurately, thus an individual no longer views their world through the lens of the trauma. A trauma survivor’s identity could be more than their trauma symptoms.

Since Herman first proposed complex PTSD, it has undergone further research and refinement. In January 2022, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases 11th Edition (ICD-11) included diagnostic criteria for complex PTSD in their manual [FN 11]. However, in the United States, complex PTSD is underdiagnosed because the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) does not recognize complex PTSD as a distinct mental health condition. [FN 12]

Trauma Exposure and Children

Research has shown that individuals are more likely to experience long-lasting effects of trauma if it occurs within the first three years of life. When traumatic experiences happen to children, crucial developmental tasks of trust and attachment are impaired. Children who have relationships with empathic caretakers who are dependable develop a secure attachment style. In contrast, when the caretakers are unresponsive, rejecting, or harmful, children learn the world is unsafe. These children may develop attachment patterns that are avoidant, anxious, or disorganized. Due to their ego-centric thinking, children often believe they are responsible for the inadequate caretaking and traumatic experiences they endured.

To fully understand children’s mental health struggles, it helps to look beyond their attachment patterns. Developmental Trauma Disorder (DTD)[FN 13] is a mental health diagnosis that more accurately describes children’s trauma symptoms. The diagnostic criteria for DTD includes a child having direct experience or witnessing violence and/or significant disruptions of protective caregiving (changes in primary caregiver, repeated separation from caregiver, or exposure to severe and persistent emotional abuse). Developmental trauma causes children to struggle with affective and physiological dysregulation, difficulty with attention, behavioral dysregulation, problems in relationships, and negative self-worth. While the DSM-5 does not include developmental trauma disorder in its manual, many trauma professionals have embraced the developmental trauma disorder diagnosis because it recognizes that children’s symptoms of trauma are different from adult trauma symptoms.

Without successful treatment of developmental trauma disorder, childhood trauma survivors often develop complex PTSD as adults. With so many adopted persons experiencing their earliest days with neglect, abandonment, foster care, orphanages, group homes, inpatient hospitalization, residential treatment, adoption dissolution, and adoption disruption [FN 14], the likelihood that adopted youth growing up and developing complex PTSD is high.

Changes In The Brain and Body Due To Traumas

A key concept to understanding the impact of trauma is that trauma victims live their lives viewing their world through the lens of the trauma long after the trauma has passed. Thus, the present is contaminated by the past. Although the brain’s intention is for the trauma symptoms to be self-protective guarding against any future traumatic experiences, it often fails to distinguish safe from unsafe people and environments.

Trauma symptoms are a normative response to abnormal events.

Understanding the basic principles of how the brain and body operate after trauma helps to understand why moving past trauma is so difficult. The emotional part of the brain (where the survival instinct resides) operates much faster than the logical prefrontal cortex section of the brain. When a threat is perceived, the body releases stress hormones, and reacts in survival mode. Each time a trauma survivor perceives a situation as threatening, the experience is reinforced in the brain—this is Hebb’s Rule: “neurons that fire together wire together.” [FN 15]. Every time a trauma-related response (e.g., hypervigilance, people-pleasing, emotional numbing, ultra-independence) is perceived to be effective, the brain becomes more inclined to use that response in the future.

Healing from trauma is not about accepting what happened or recalling every detail. Talking about traumatic events and symptoms alone is often insufficient to remove their imprint, because the region of the brain responsible for speech is not directly connected to the area where trauma memories are stored. Healing involves learning how to quiet the imprint of trauma.

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms Seen In Adoption Triad Members

Not every birth parent, adopted person, or adoptive parent will experience the same trauma symptoms, as each individual’s response to severe stress is shaped by their unique DNA and lived experience. Factors such as the number of traumatic experiences, biological predispositions, availability of support, and intergenerational issues all play a role in the development of a trauma disorder. As discussed earlier in this blog post, the long-lasting effects of trauma determine whether an event results in a trauma diagnosis. The same event (e.g., closed adoption) may be traumatic for one member of the adoption triad, while another may find it as a negative in their life, but not experience it as traumatic.

Research has repeatedly shown that having supportive people present at the time of a traumatic event is often the best predictor of whether trauma symptoms develop. Conversely, a lack of support during the traumatic event increases the likelihood of trauma symptoms.

The first four symptom categories discussed below (intrusive symptoms, avoidance of stimuli, negative alterations of cognitions or mood associated with the event, and alterations in arousal and reactivity) are seen in individuals with both post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD). The diagnostic criteria for complex post-traumatic stress disorder includes three additional trauma symptom categories: relationship difficulties, dysregulation, and negative self-worth.

Please keep in mind, the trauma symptoms below are for general information purposes only. The full diagnostic criteria for complex PTSD is not outlined in this blog post, as diagnosing should only be done by a trained mental health professional.

Intrusion Symptoms

Intrusion symptoms are recurrent, involuntary, and distressing memories, dreams, images, or thoughts associated with the traumatic events. Physiological or psychological distress occurs when there is an internal or external cue that the brain reacts to as a reminder of the traumatic event. The trauma survivor may or may not be able to identify what the trigger was; they only know their brain and body are reacting. An example is the adoptee who dislikes their birthday because the occasion triggers thoughts of their relinquishment and loss of their birth family.

One type of intrusion symptom is dissociative reactions (e.g. flashback) when a trauma survivor feels or acts as if the trauma were happening in the present. For an adoption triad member, this intrusive symptom can be an unrealistic fear of losing someone. This is seen in reunion contact when adoptees or birth relatives have intense stress around separation and/or lack of contact because it emotionally feels like they are losing their relative, just like they did at the time of the original estrangement. It can also be a birth mother who is overprotective of subsequent children or an adopted child with separation anxiety.

Intrusive symptoms may appear as dreams. An example is when a birth mother has nightmares of their child being taken from them, or nightmares of losing a child. Adoptive parents who fear that they are not the “real” parents may believe adoptive families are inferior to families formed by birth. This may result in intrusive thoughts that talking about the birth family will make their child want to look for birth relatives, resulting in them avoiding all talk of the birth family.

The intrusive symptoms can also come out as a preoccupation with the source of the trauma. A common example of this is when an adoptee or a birth parent is obsessed with an idealized vision of a reunion with their estranged relative. Excessive details of the fantasy relationship develop when they do not even know their relative.

Avoidance of Stimuli

Examples of avoidance of stimuli in PTSD include not driving on highways after a serious car accident or avoiding loud noises after experiencing explosions. This avoidance of stimuli occurs because talking about or being near reminders of the traumatic experience can trigger unwanted thoughts, memories, or emotions. Among adoption triad members, the most common form of avoidance is not thinking or talking about the impact of relinquishment and adoption.

When the “support system” does not want to hear about the feelings related to relinquishment and adoption, the survival strategy becomes avoiding all discussion of the traumatic experiences. Avoidance happens when there is a belief that adoptive families are “the same” as families formed by birth, therefore, adoption cannot be a source of distress. It can also be a response to a betrayal trauma, e.g., if you love a family member and want to continue your relationship with them, it may be too painful to acknowledge the family member was the source of the trauma. Most birth mothers rarely talk about the trauma they have endured because it is too triggering. A birth parent whose family did not help them keep their child may not want to think about the pain caused by their family to avoid estrangement.

Children who experienced early neglect (including time in foster care or an orphanage) or physical abuse may avoid attaching to new adoptive parents. Dan Hughes calls this the Child who Mistrusts Good Care [FN 16]. If an individual believes that people are not safe or that people always leave, it can cause the trauma survivor to keep people at an emotional distance. Some adoptees end relationships, even when the relationship is going well, because they want to leave the relationship before the person leaves them, due to fears of abandonment. Ultra-independence can be a form of avoidance of closeness in relationships.

Dan Hughes Lecture on the Child Who Mistrusts Good Care

Avoidance of stimuli for an adoptee may be to not think negatively of their adoptive parents’ lack of support on adoption issues, based on their belief that their life would have been far worse had they not been adopted. Adoptee avoidance can include believing that spending time in an orphanage or infant home had no impact on them, even when they have complex PTSD symptoms. Adoptees often do not talk with their adoptive parents about what it feels like to be adopted unless they are confident they will be supported. Having already lost one family due to adoption, adoptees will not risk losing a second family by upsetting their adoptive parents.

Adoptive parents’ avoidance of stimuli can include avoiding any acknowledgment that their child’s birth family exists. For some, it is too painful to emotionally accept that their child has another set of parents and an extended birth family. They often fear that their child will not be close to them if they acknowledge their child has family members, traits, and medical history that is not theirs. This is the opposite of what research on adoptive families has shown [FN 18]. This can lead to an adoptive parent telling their child they are disloyal for speaking about their birth family. When adoptive parents are traumatized by their child with significant attachment issues rejecting them, they may create an emotional distance from their child, who continuously rejects them. This is referred to as the parent having blocked care.

Avoidance of stimuli also appears in adoption reunion. When contact between birth parent and adoptee is so emotionally overwhelming, they may avoid all or only emotionally tolerate minimal contact because it is too triggering. This explains why adoptees sometimes find it easier to maintain a relationship with an extended birth family member than their birth mother. The extended family member most likely does not have trauma experiences from the crisis pregnancy and relinquishment as the birth mother, and therefore they are not being triggered by contact with the adoptee. Some adoptive parents’ avoidance is shown by their initiating estrangement when their adopted child has contact with their birth family.

In open adoption, avoidance of stimuli happens when the birth parent ceases all contact with the adoptive family. It is too painful to witness someone else parenting their child, which is beyond heartbreaking. Adoptive parents may assume the birth parent simply “moved on”, but in reality, the birth parent stopped contact because it was too emotionally triggering. Conversely, adoptive parents may also end contact in open adoption because continued contact with the birth parent is too emotionally overwhelming.

In The Fog As A Trauma Response

The adoption community uses the term “in the fog” and “adoption consciousness” [FN 16] to describe an adoption triad member who avoids thinking and feeling about the impact of adoption on them. For some, the lack of awareness is an aspect of their personality that is not introspective or a lack of connection to their feelings. For other adoption triad members, in the fog may be a trauma avoidance symptom. Using the 3 E’s paradigm for guidance, being in the fog becomes a trauma symptom when a triad member relies on the avoidance strategy as an emotional defense against overwhelming feelings related to loss, identity, or other core issues of adoption. The lack of adoption consciousness becomes a means of emotionally containing the overwhelming emotions.

In addition to the avoidance of stimuli for individuals with complex PTSD, an individual may also avoid acknowledging that they have been traumatized. Several factors can contribute to this avoidance:

-Fear that acknowledging the trauma and its symptoms will cause them to “go crazy,” completely break down, or become unable to function.

-Fear of losing their sense of identity, as trauma symptoms have been internalized as part of who they are.

-Denial of the trauma helps maintain a relationship with the perpetrator, who is often a family member. It can feel safer to hold a distorted perception of the person who caused the trauma than to risk disapproval or estrangement.

Negative Alterations of Cognitions or Mood Associated with the Event(s)

Negative alterations of cognitions or mood include aspects of memory, inaccurate beliefs, emotions, and feelings of detachment. When a trauma is so overwhelming, the brain can suppress an entire event, aspects of the event, and the perpetrator. Many birth mothers report amnesia of the time they were pregnant and the delivery of the baby due to the survival response of dissociation. Birth mothers may not remember the date of their child’s birth. If an individual is in a relationship with the perpetrator, often a family member, to survive they must have amnesia of how hurtful the perpetrator was to maintain the relationship that is needed for survival.

Negative cognitions can include persistent and exaggerated negative beliefs or expectations about oneself, others, or the world. This includes beliefs of “I am bad”, “No one can be trusted”, or “The world is completely unsafe”. Often, this is where the discomfort with compliments comes from. If the trauma survivor believes they are a bad person, then the compliment is contrary to their belief that they are a bad person. Birth parents feel they are a horrible person for not raising their child, while minimizing the impact of family, the business of adoption, and society on not helping them to keep their child.

Persistent, distorted cognitions about the cause or consequences of the traumatic event(s) can lead an individual to inaccurately blame themselves for the traumatic event. This is more likely to happen if the trauma happened during childhood or the perpetrator is a loved one. Children are ego-centric in their thinking, so they believe they cause bad things to happen to them. Adoptees may believe they kicked too much in utero, were an ugly baby, or a difficult newborn, and that is why they did not stay with their birth mother. Trauma survivors often believe they are inherently bad because why else would a loved one be cruel to them?

When family members deny the negative impact of adoption, it results in individuals feeling that no one can be trusted. The trauma symptoms of fear and hypervigilance interfere with an individual feeling safe, even when they are with safe people in a safe environment.

Often, trauma survivors have a persistent negative emotional state of fear, anxiety, guilt, or shame. Adoptees can feel the profound shame of being adopted, even with having no part in the decision of relinquishment. Trauma survivors can feel shame for not being enough for their family members. Profound shame causes poor self-worth, resulting in the false belief that the trauma survivor does not deserve to be happy or have good things happen to them. With guilt and shame regularly experienced by adoption triad members, guilt and shame are included in the adoption paradigm the core issues of adoption.

A persistent feeling of fear can cause an adoption triad member to engage in people-pleasing behaviors or act like a” chameleon” to ward off perceived fear of rejection. This happens because the trauma victim has no control over others, but they believe they ward off stressful and negative interactions by acting in a manner that with make others happy with them. For birth parents and adoptees, this can look like the loyal family member who does not talk about the traumatic impact of relinquishment and adoption. The price of these trauma symptoms is a diminished sense of personal identity, as individuals suppress their true feelings, needs, and hopes.

Many trauma symptoms interfere with the ability of an individual to experience positive emotions (e.g. inability to experience happiness, satisfaction, or loving feelings). This could happen because the trauma belief that “all feelings are bad” shuts down the positive feelings as well as the negative feelings. For others, it could be that they believe they do not deserve good things to happen to them, so subsequently, they are not entitled to positive feelings and experiences.

The negative alterations in cognitions and mood often lead trauma survivors to have a diminished interest or participation in significant events.

Marketed Alternations in Arousal and Reactivity Associated with the Traumatic Event(s)

Marked alternations in arousal and reactivity include: irritable behavior and angry outbursts with little or no provocation. This can be verbal or physical aggression towards others, objects, or themself. Reckless, self-destructive, and self-harming (e.g. cutting) behaviors help trauma survivors to regulate their nervous system due to the release of adrenaline, dopamine, serotonin, endorphin, or other neurotransmitters.

While many adoption triad members feel the world is unsafe because of the horrible things they have experienced, it is not unusual for hypervigilance to lead to an overgeneralization that everything and everyone is unsafe. This interferes with the trauma survivor’s ability to accurately assess situations or people for safety. Additionally, trauma survivors can also struggle with sleep disturbances, concentration, and an exaggerated startle response.

Three Additional Trauma Symptom Categories Seen in Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Negative Self-Integrity

Individuals with complex PTSD have negative self-worth beyond what individuals with PTSD experience. Their internal dialogue is more directed to themselves as being a horrible human being than an individual who is flawed due to their trauma symptoms. The self-loathing is so severe that they do not believe they deserve good things to happen to them or to be happy.

A birth mother who was rejected by family, friends, and society may believe that their unplanned pregnancy and subsequent relinquishment mean they should be treated horribly for the rest of their lives. The adopted child with a developmentally ego-centric view of the world, may internalize that something is wrong with them to have been estranged from their first mother and birth family. Adoptive parents who are raising children with trauma experiences, whose trauma reactions include keeping emotional distance from them, may believe they are bad because their child rejects their love and care.

Negative self-integrity includes difficulty being grounded in reality. An adopted person can believe they deserve to have their feelings and needs minimized by their adoptive parents because where would they be if the adoptive parent hadn’t taken them in? For the adoptive parent who mentally cannot acknowledge the existence of the birth family, the fantasy is that their child’s birth family and history do not exist in their consciousness.

Affect Dysregulation-Small Window of Tolerance

The term window of tolerance was coined by Dr. Daniel Siegel [FN 19] to describe an emotional zone where individuals can manage their emotions and actions productively. When individuals are in their window of tolerance, they are aware of their body sensations, can identify their feelings, and think abstractly. Individuals with a wide window of tolerance can ride the waves of their emotions when stressed without shutting down or overreacting. If someone has a history of high stress, it is common for them to have a smaller window of tolerance. The horrific stress of the trauma event(s) and lack of support at the time of the trauma have changed trauma survivors’ brains and bodies, resulting in their no longer being able to manage stress effectively. Minor stress can cause the trauma survivor to overreact or underreact. Recovering from stressful episodes can be unusually long.

Hyperarousal is the term for the dysregulated state of over-arousal. Hyperarousal may result in defensiveness, anger, flight, hypervigilance, racing thoughts, intrusive imagery, emotional outbursts, and agitation. An analogy for a person in hyperarousal is as if their body is like a pot with simmering water on a stove. It does not take much heat to send the water in the pot to boil over. Hypoarousal is the term for the dysregulated state of under-arousal. Examples of a person in under-arousal include spacy, losing track of time, sluggishness, absence of emotions, numbness, frozen, emotionally, or physically shut down. An analogy for a person in hypoarousal is as if the body is like an ice cube tray with ice-cold water. When the ice cube tray is placed in the freezer, the water will turn into solid ice cubes quickly. When the emotional pain becomes intense, suicide ideation happens. It is not that people want to die; they do not know how to live with the intense pain.

Trauma survivors can be so hypervigilant about getting stressed that they will make exorbitant efforts to avoid stress. One way this is done is to become numb to feelings. The suppression of feelings is referred to as alexithymia. Their brain and body have internalized that it is not safe to feel, so the coping mechanism is to be numb. Being numb to feelings increases the likelihood of revictimization because the individual is not in touch with internal cues to unsafe situations.

Dissociation is a mental ability that instinctively happens during high-demand situations or when our attention becomes unfocused. Dissociative behaviors are on a continuum. On one end of the continuum are healthy/normal dissociative responses of daydreaming, getting lost in thought, and highway hypnosis when the driver spaces out on the specifics of a long trip. The other end of the continuum is the dissociation that results from hypoarousal. It happens in degrees, and the severity is usually a reflection of the level of stress.

Individuals who use dissociation are more likely to have been unable to leave the traumatic event when it occurred. When the brain and body found the terror too overwhelming to be emotionally present, the survival response used was dissociation. It is so effective in alleviating stress that many individuals use dissociation instinctively to minor stressors.

Examples of dissociative behaviors include fantasy, numbing, being spacey, and being overly absorbed in an activity. Some trauma survivors will spend excessive time sleeping. Addictive behaviors (alcohol, drugs, eating disorders, excessive online and gaming) are often the result of a need to feel numb. Dissociation may happen as depersonalization and derealization. Depersonalization is when a person feels detached, as if they are an observer of their mental processes or body. Derealization is when a person experiences unreality of surroundings – unreal, dreamlike, distant, or distorted. At the far end of the dissociation continuum, dissociation involves splitting into protective parts that involve significant memory lapses and significant compartmentalization. When this happens, individuals will find they do not have memories of how they got somewhere, have no memory of buying things, or forget how they ability to do something. Dissociation can be significant enough for a trauma survivor to have a dissociative disorder.

Relationship Difficulties

Survival strategies of not trusting, isolation, and being overly independent interfere with developing relationships. This can result in a tendency to avoid, deride, or have little interest in relationships or social events. Sometimes, the opposite happens with trauma survivors requiring constant reassurance. Fears of loss, rejection, and abandonment cause neediness. Not knowing how to reassure themselves, individuals look to others to reassure them. The trauma survivor who fears abandonment may feel like an argument is intolerable because a terminated relationship means the unbearable pain of being alone. Adoptees who struggle with fears of being alone will identify a future partner before they terminate their current relationship, thus allowing them to immediately start the next relationship and avoid being alone.

Trauma survivors who use being a people pleaser (fawn response) or chameleon (behaving in a manner to fit in and be liked) result in them not being genuine in their relationships. This strategy sacrifices the self. The survivor becomes disconnected from their feelings, needs, and beliefs as they focus on others’ happiness and ignore their needs. In losing their voice, they lose their identity.

With no self-worth, trauma survivors may only feel comfortable in a relationship with a person who is unkind to them. Birth mothers have shared they felt like such a horrible person for not raising their child, they married someone who was physically or psychologically abusive because they did not think they deserved better. It is not unusual for an adoptee to discontinue pleasurable romantic relationships because they will leave the relationship before the person leaves them.

Summary of Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Trauma Symptom Categories

The seven complex post-traumatic stress disorder symptom categories described in this blog post are the diagnostic categories seen in the diagnostic manuals and research. The categories are needed so there is a rudimentary agreement of C-PTSD symptoms for treatment, discussion, research, and insurance reimbursement. Trauma survivors’ symptoms are personal experiences and are nuanced for every individual.

Adoption triad members may find the trauma symptoms in the diagram below a more useful description of their symptoms

Additional Health Struggles

Individuals who have experienced extensive trauma may have additional mental health struggles. This may include anxiety disorders (OCD, severe phobias), eating disorders, addictions (substance misuse disorders), depression disorders, and personality disorders (dissociative identity disorder [FN20], borderline personality disorder). Trauma survivors have higher rates of heart disease, arthritis, chronic pain, and gastrointestinal problems.

Conclusion

The hope of this blog post is to give the reader a better understanding of the connection between adoption traumas and complex post-traumatic stress disorder. With acknowledgment that psychoeducation on trauma is not enough to rewire a traumatized brain, readers who would like to learn more about healing from complex PTSD may benefit from learning about:

1) The Three Stages of Treatment for Complex PTSD

2) The Differences Between Top-Down Versus Bottom-Up Psychotherapy

3) Stress Management Techniques for Widening the Window of Tolerance for Stress blog post

4) Books written for trauma survivors

Transforming the Living Legacy of Trauma: A Workbook for Survivors and Therapists by Janina Fisher

A Practical Guide to Complex PTSD: Compassionate Strategies to Begin Healing from Childhood Trauma by Arielle Schwartz

Live Empowered: Rewire Your Brain’s Implicit Memory by Julie Lopez (an adopted person)

Attachment and Trauma Network for information on developmental trauma and trauma therapies for youth

Individuals who believe they have complex PTSD should seek out the help of a trained trauma therapist for a diagnosis, treatment plan, and trauma-informed therapy.

A subsequent blog post on the 3 stages of trauma-informed psychotherapy for complex post-traumatic stress disorder is planned for 2026. Follow Marie on social media (links below) to learn about Marie’s speaking events and new blog posts.

Wishing everyone the best on their healing journey.

Marie

Copyright © 2025 Marie Dolfi, LCSW. All rights reserved

Footnotes

1 The 3 Es of Trauma, The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration https://library.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/sma14-4884.pdf

2 Vinke, A.J.G., (2020). Intercountry Adoption, Trauma, and Dissociation: Combining Interventions to Enhance Integration, European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 4(4); Reyka, J., (2019). Treatment Considerations for Adoption-Related Complex Trauma- Dissertation, Digital Communications @ NLU; Child Abuse & Neglect Journal special issue on adoption and trauma, vol. 130 (part 2), August 2022

3 van der Kolk, B., (2014). The Body Keeps the Score, Viking; Schwartz, A., (2021). The Complete PTSD Treatment Manual: An Integrative, Mind-Body Approach to Trauma Recovery, PESI Publishing; Fisher, Janina (2021), Transforming the Living Legacy of Trauma: A Workbook for Survivors and Therapists. PESI Publishing and Media

4 Adoption microaggressions can be intentional, or unintentional slights, insults, or aggressive actions that communicate negativity or judgment towards adoption triad members. Microaggressions can impact their sense of belonging, identity, and induce shame. Garber, K. J., (2014, February). “You Were Adopted?!: An Exploratory Analysis of Microaggressions Experienced by Adolescent Adopted Individuals”. Masters Theses, University of Massachusetts Amherst; Baden, A. (2016). “Do You Know Your Real Parents” and Other Adoption Microaggressions, Adoption Quarterly, 19(1), 1-25.

5 Coussons-Read ME., Effects of prenatal stress on pregnancy and human development: mechanisms and pathways. Obstet Med. 2013 Jun;6(2):52-57.

6 Yehuda, R.; Lehrner, A. (2018). Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. World Psychiatry, 17(3), 243-257.

7 Freyd. Freyd, J.J. (1994). Betrayal-trauma: Traumatic amnesia as an adaptive response to childhood abuse. Ethics & Behavior, 4, 307-329 and nd Freyd, J. J. (1996). Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

8 Herman, J., (1992). Trauma & Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror, Basic Books.

9 The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study was a collaborative research effort between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente, investigating the link between childhood trauma and long-term health outcomes. Findings showed that adverse childhood experiences are strongly associated with increased risk for various physical and mental health problems later in life. Details of the study can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

10 Shapiro, F., (2018). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures 3rd edition, The Guildford Press

11 WHO Complex PTSD https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en#585833559

12 The DSM V is the diagnostic manual of psychiatric conditions published by the American Psychiatric Association.

13 Developmental trauma disorder Attachment and Trauma Network Developmental Trauma Disorder https://www.attachmenttraumanetwork.org/developmental-trauma-disorder/

14 Adoption disruption and dissolution both involve the end of an adoption. Disruption occurs before finalization, dissolution happens after the adoption is legally finalized.

15 Hebb’s Rule was described in Hebb, D. O. (1949). The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory. Wiley.

16 Hughes, Dan (2015, January 29). The Child That Mistrusts Good Care, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xuRagD9ES9w

17 Branco, S. F., Kim, J., Newton, G., et al. (2022). Out of the Fog and into Consciousness: A Model of Adoptee Awareness https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362643073_Out_of_the_Fog_and_into_Consciousness_A_Model_of_Adoptee_Awareness

18 Kirk, H. D., (1984). Shared Fate: A Theory and Method of Adoptive Relationships, Revised Edition, Ben-Simon Publication

19 Window of Tolerance Siegel, D. J. (1999). The Developing Mind: Toward a Neurobiology of Interpersonal Experience. Guilford Press.

20 Information on dissociative identity disorder can be found at https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11185985/